Editorial Focus

This Compendium presents an eclectic exploration of the mythologies surrounding us in our every-day lives. Our research focus blends curiosity with informal academic inquiry. It remains inherently incomplete. Entries are editorial and speculative in focus and not intended to replace expert or peer-reviewed work.

Further Exploration

Most entries include links to text, audio and video resources. All are shared from public domain media, archives and organisations.

Scholarly

For deeper inquiry, Ask AI.SOP citations provide access to a range of open access academic papers, archives, and libraries.

Community

MythCloud welcomes the submission of content proposals from the wider public to expand both our Compendium (Explore) and AI.SOP Knowledge base (Ask) repositories. Further details available on our Contact page.

Discover the MythCloud

This woodblock from 1652, crafted by Christoffel Jegher (c. 1596-1653), features the printer's mark of the prestigious Plantin Press (Officina Plantiniana), one of the most significant printing establishments in 16th and 17th century Europe. Now preserved in the Museum Plantin-Moretus in Antwerp, Belgium—a UNESCO World Heritage site—this artefact represents the intersection of visual symbolism, commercial identity, and early modern print culture.

The design includes a compass held by a hand emerging from a cloud, flanked by two allegorical figures: Hercules symbolising labour (Labor) and a female figure representing constancy (Constantia). This iconography encapsulated the press's motto: "Through work and constancy," reflecting the values of its founder, Christophe Plantin, and his successors, the Moretus family.

The mark served as both a commercial logo and a symbolic representation of the press's commitment to precise, consistent work. Used in notable publications such as various editions of the Breviarium Romanum, this visual identifier helped establish the Plantin Press's reputation for quality across Europe during a period when books were becoming increasingly central to knowledge dissemination.

Jegher, a master woodcutter who collaborated with Peter Paul Rubens on numerous projects, brought exceptional craftsmanship to this small but significant piece. His technical skill exemplifies the artistic standards maintained by the press, where visual and textual elements were integrated with equal attention to detail and quality.

The block stands as a testament to the development of brand identity in early modern publishing, demonstrating how symbolic visual language was deployed to communicate values and establish recognition in an expanding marketplace of printed materials.

Fontaines D.C. represent a fascinating contemporary adaptation of Irish literary traditions into musical form, demonstrating how mythological thinking evolves through new media while maintaining connection to established cultural frameworks. By channeling the linguistic explorations of Joyce, the social critiques of Kavanagh, and the existential investigations of Irish literature into post-punk musical expression, the band creates a compelling synthesis of traditional and contemporary approaches to cultural storytelling.

The band's emergence from Dublin's literary culture reflects the continuing vitality of Ireland's literary heritage as a resource for addressing contemporary experience. Rather than merely referencing literary predecessors, Fontaines D.C. adapt core elements of Irish literary tradition—careful attention to language, engagement with place, exploration of identity—to create musical expressions that respond to contemporary urban experience. This process exemplifies how effective cultural mythology evolves through creative reinterpretation rather than mere preservation.

Particularly significant is the band's exploration of Dublin's psychological landscape through rhythmic language and introspective lyrics. By rendering urban experience through carefully crafted verbal and musical frameworks, their work continues the tradition of Irish writers who have transformed specific locations into universal metaphors for human experience. This transformation of physical environment into mythological landscape demonstrates how contemporary artists continue to create meaningful frameworks for understanding place-based identity in rapidly changing urban contexts.

The band's engagement with Ireland's literary mythologies represents a form of cultural archaeology, uncovering and reinterpreting elements of shared cultural memory for new audiences and circumstances. By translating literary approaches into musical form, they create multisensory experiences that engage audiences emotionally and intellectually, demonstrating how mythological thinking continues to evolve through medium-specific adaptations. Their work exemplifies how contemporary artists maintain dialogue with cultural traditions not through imitation but through creative transformation that addresses present concerns while acknowledging historical continuity.

Pauline Lebbe's analysis of Belgian art songs set to symbolist texts offers valuable insights into how mythological thinking adapted to modernist artistic contexts. During the period between the 1880s and the Second World War, Belgium became a creative crucible where literary symbolism—with its emphasis on suggestion, evocation, and transcendence—found powerful musical expression through art songs that created new mythological frameworks for understanding human experience.

The collaboration between musicians, artists, critics, theorists, and concert organisers described by Lebbe exemplifies how cultural mythologies emerge not from isolated genius but from complex creative ecosystems. These interconnected networks facilitated the cross-pollination of ideas across different artistic disciplines, producing innovative works that responded to the spiritual and existential challenges of modernity while drawing on both traditional and newly invented symbolic languages.

Symbolist art songs, though less well-known than their literary and visual counterparts, represent a significant adaptation of mythological thinking to modern artistic forms. By combining evocative texts with sophisticated musical settings, these compositions created multisensory experiences that functioned similarly to traditional mythological narratives—providing frameworks for understanding aspects of experience that resist literal description while evoking emotional responses that transcend rational comprehension.

The rich collaborative environment Lebbe describes demonstrates how mythological thinking continued to thrive in ostensibly secular, modernist contexts. Rather than abandoning symbolic understanding in favour of scientific rationalism, these artists created new mythologies that addressed the psychological and spiritual needs of a rapidly changing society. This cultural moment offers valuable perspective on how mythological thinking continually reinvents itself to remain relevant in new contexts, adapting traditional symbolic languages while developing innovative forms of expression.

This traditional Lithuanian folk song, documented by Jonas Basanavičius (1851-1927) as part of his extensive fieldwork collecting Lithuanian cultural expressions in the late 19th century, represents a significant element of Lithuania's intangible cultural heritage. The preservation of such folk songs was particularly important during a period when Lithuanian national identity was under pressure from Russification policies imposed by the Tsarist regime.

Basanavičius, often referred to as the "Patriarch of the Nation," played a central role in the Lithuanian National Revival movement, recognising that cultural expressions like folk songs were essential repositories of linguistic tradition and collective memory. His systematic documentation of songs and tales from villages across the Lithuanian-speaking territories created an invaluable archive of cultural knowledge that might otherwise have been lost to modernisation and political suppression.

The song's title, which translates as "A Warm, Beautiful Little Autumn," immediately establishes its connection to seasonal rhythms and agricultural life. Lithuanian folk songs typically reflect the deep relationship between rural communities and the natural environment, marking transitions between seasons and acknowledging the importance of weather patterns for agricultural prosperity.

The diminutive form used in the title (rudenėlis rather than rudenis) is characteristic of Lithuanian folk expression, where diminutives express affection and intimacy rather than simply indicating small size. This linguistic feature creates a sense of familiar, personal relationship with natural phenomena and seasonal cycles.

The preservation of this cultural expression by the Lithuanian Literature and Folklore Institute's Lithuanian Folklore Archive ensures continued access to these traditions, maintaining connections between contemporary Lithuanian society and its pre-industrial cultural heritage. This institutional commitment to preserving oral traditions reflects the recognition that such expressions contain valuable insights into historical relationships between communities and their environments.

This woodcut titled "Haemorrhous," depicting a mythological snake, exemplifies how early modern scientific texts incorporated fantastical elements alongside empirical observations. Created by designer Geoffroy Ballain and woodcut artist Jean de Gourmont in 1565 for Jacques Grévin's works on poisons and venomous creatures, this image demonstrates the complex relationship between mythological thinking and emerging scientific methodology in Renaissance natural history.

The Haemorrhous snake's inclusion in texts discussing natural poisons reveals how the boundaries between observed and imagined phenomena remained fluid in early scientific literature. Rather than representing failed empiricism, this integration reflects a worldview that understood nature as potentially containing wonders beyond everyday experience. The snake's name, suggesting connection to blood and haemorrhage, demonstrates how nomenclature itself often carried symbolic meanings that shaped understanding of natural phenomena.

The woodcut technique allowed for detailed visual representation in printed materials, playing crucial role in standardising and disseminating knowledge of both real and mythological creatures. This technological innovation transformed how information circulated, creating increasingly stable visual references that shaped collective understanding of natural and supernatural phenomena. The intricate execution of this particular woodcut demonstrates the era's commitment to precise visual documentation even of creatures whose existence was uncertain.

The woodcut's acquisition by the Plantin-Moretus Museum in 1876 represents another phase in its cultural evolution—from practical printing element to preserved historical artifact. This transition reflects changing attitudes toward early scientific materials, which came to be valued not just for their content but as evidence of evolving approaches to knowledge classification. The image thus provides valuable insight into how Renaissance culture navigated the complex relationship between observation and imagination in developing early modern natural history.

The Irish flag's history offers insights into how visual symbols shape national narratives. From green fields with golden harps to today's tricolour, these emblems create visual shorthand for complex historical narratives and cultural values.

Early Irish flags used Gaelic iconography, particularly the green field with golden harp, linking modern national aspirations to ancient heritage. By using pre-colonial symbols, these flags positioned independence movements as restoring historical sovereignty rather than creating new political entities. This exemplifies how nationalist movements construct mythologies connecting contemporary struggles to idealised historical precedents.

The tricolour's introduction in 1848 by Thomas Francis Meagher represents a sophisticated attempt to address Ireland's religious divisions. Inspired by the French revolutionary tricolour, Meagher's adaptation reflected Ireland's revolutionary aspirations while addressing its unique social landscape. Incorporating green (Catholics/Nationalists), orange (Protestants/Unionists) and white (peace between them), this design articulated an aspirational vision of unity that acknowledged divisions while suggesting possible reconciliation. The tricolour functioned not simply as representation but as visual articulation of a desired future.

The flag gained deeper meaning through historical events, particularly its association with the 1916 Easter Rising. Flying above the General Post Office during the rebellion, it first became linked with narratives of sacrifice and resistance fundamental to Irish independence mythology. The Rising's leaders embraced collective struggle for the public good, aspiring to create an Ireland serving all citizens equally. In later decades, this symbol experienced problematic recontextualisations by Republican paramilitaries during the Troubles and more recently by elements of Ireland's emerging far-right movements.

This evolution shows how symbols develop through historical contexts rather than formal design alone, acquiring complex resonances that both reflect and shape collective identity, sometimes contradicting their original aspirational meaning.

—

We Can't Let The Far Right Claim Our Tricolour

District Magazine, April 2025, Instagram, Dray Morgan (Extract)

It's unsettling, it's saddening but it's also disgraceful. Irish iconography used to promote a fundamentally non-Irish sentiment. The Tricolour left bismerched and Irish culture being overlooked for the sake of racism and xenophobia. Don't let the far right claim our Tricolour. There's no denying that the scenes from Saturday's anti-immigration protest were unsettling. Equally as striking is the choice of iconography by right-wing demonstrators when disseminating a fundamentally non-Irish sentiment.

Tri-colours and harps were ever-present throughout the crowds, combined with chants of "Get Them Out" and other xenophobic slogans.

Here are some reasons why the Irish Tricolour and other iconography doesn't and will never align with anti-immigration and far-right rhetoric.

The History of the Tricolour: The Irish Tricolour came to fruition in 1848, when the leader of Young Irelanders, Thomas Francis Meagher, received the flag from a group of French women in Paris. The flag symbolised solidarity with the Irish cause against the British oppressors, as well as peace between Catholics and Protestants. The Tricolour did not become Ireland's national flag until 68 years later in 1916. Until then, it served as an international sign of solidarity between Ireland and other nations, a progressive symbol which sought equality and resistance from discriminatory regimes.

This was also the era in which Ireland saw its greatest emigration in its history. The Great Hunger saw over 2.5 million people forced to leave their homes and emigrate across the world, spreading Irish iconography and culture globally. Ireland's population decreased heavily from 6.55 million to 4.23 million, rendering those who left effective humanitarian refugees.

Imported Ideology: Anti-immigration has and never will be an ideology of the Irish. It is, of course, impossible to ignore the fact that Ireland has the largest diaspora per capita of any nation in the world. 80 million people outside of Ireland claim Irish ancestry. We are a nation of emigrants.

Furthermore, imported ideologies are filtered through social media into the Irish psyche. This was only exemplified by the MAGA sympathisers and even imagery of Vladimir Putin at Saturday's demonstration. In May 2024, The Journal reported on more than 150 social media accounts that were claiming to be Irish but were operated by non-Irish users. Accounts like these contribute heavily to a rising ethno-nationalistic and racist view. Irish social media users are unknowingly being influenced by foreign entities.

A Sinister Core: At the core of anti-immigration Ireland, is a truly sinister underbelly that operates through Telegram channels, with rhetoric led by unwavering racism and fringe ideologies. Figureheads such as head of the extremist far-right National Party, Justin Barrett (who was present at Saturday's rally) spew admiration for Nazi ideology as well as pushing misinformation and conspiracy theories. This has led to fringe groups such as Clann Eireann, a racist group with almost 3,000 members on Telegram. From 2020 to 2023, mis and disinformation in Irish Telegram channels rose by 326%.

Take Off Those Celtic Jerseys: Multiple Celtic jerseys were seen at the protest. Celtic F.C. was created in 1888 for the purpose of creating a club for Irish immigrants and alleviating the poverty experienced by the Irish community in Scotland. A driving factor of Celtic's ethos is acceptance, humanity and equality. Championed as a club for the oppressed and a haven for the othered, a Celtic jersey will never represent the racist and unwelcoming ideology of the far-right. Gil Heron, Celtic F.C's first black football player and father to Gil-Scott Heron, renowned musician and writer of "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised".

Do You Really Want To Be Like Them? Looking at our British neighbours, the St. George's flag has been ruined by years of bigotry, discrimination and hatred being flown under the banner of the image. Far-right groups on both sides of our seas have appropriated their national flags, giving it connotations of hate and fear. We cannot let this happen to the tricolour, a symbol of hope, peace and a piece of Irish iconography for all to be proud of. We can't let the far right claim our Tricolour.

"The Tricolour will be a right-wing symbol soon if it's not front and centre at counters. Being allergic to your own flag is moronic and damages your legitimacy as a national movement. A sea of red and pink flags without the hard won symbols of Irish nationalism plays into the right-wing narrative that left is inherently anti-Irish. Fly the tricolour if you don't want it to end up like the St Georges flag in England."

Irish artist Spice Bag

Instagram: @district.magazine; Writing @dray.morgan; Photography @hasanyikiciphotography; Additional; @hasanyikiciphotography @gregbyrnephoto @spicebag.exe

These Baltic brass rings featuring serpent motifs exemplify how mythological understanding was literally worn on the body in traditional societies. Inspired by archaeological findings throughout the Baltic region, these rings transform abstract cosmological concepts into tangible, personal objects that connected individuals to broader cultural narratives.

The serpent, a potent symbol in Baltic mythology as in many world traditions, functioned as a multivalent emblem associated with protection, fertility, and cyclical renewal. Its ability to shed its skin made it a natural symbol of transformation and rebirth, while its movement between surface and underground realms positioned it as a mediator between worlds. The specific association with justice, happiness, and domestic safety suggests the serpent's role as a guardian of proper order in both cosmic and social domains.

Beyond their symbolic content, these rings served as personal talismans, believed to channel protective powers for the wearer. This apotropaic function illustrates how mythological thinking in traditional societies extended beyond abstract belief into practical engagement with supernatural forces through material objects. The wearing of such symbols represented both cultural affiliation and active participation in a world understood to be animated by unseen forces.

The contemporary reproduction of such designs demonstrates how mythological symbols maintain cultural resonance even when detached from their original belief contexts, serving as tangible connections to ancestral worldviews. These seemingly modest objects thus function as repositories of cultural memory, linking past and present through persistent symbolic forms.

The Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp (KMSKA) houses an ink drawing titled Pegasus, Inventory No. 3265/8, by Alfred Ost (1884-1945), a Belgian artist known for his distinctive graphic style and particular interest in animal subjects.

This drawing depicts the mythical winged horse from Greek mythology, a creature with a rich symbolic history spanning thousands of years of cultural development. In classical mythology, Pegasus emerged from the blood of the Gorgon Medusa after she was beheaded by the hero Perseus. The winged horse has most famously been associated with the hero Bellerophon, who captured and rode Pegasus in his quest to defeat the monstrous Chimera.

Beyond heroic narratives, Pegasus is traditionally linked to poetic inspiration. According to myth, he created the spring Hippocrene on Mount Helicon with a strike of his hoof, establishing a fountain that granted poetic inspiration to those who drank from it. This association led to Pegasus becoming a symbol of artistic inspiration and the transcendent power of imagination across Western cultural tradition.

Ost's rendering likely captures the dynamic essence of this mythical creature, emphasising its elegance and power through the expressive potential of the ink medium. The artist's known affinity for portraying animals with sympathy and insight would have informed his approach to this mythological subject.

The drawing represents the continued resonance of classical mythological figures in modern artistic practice, demonstrating how ancient symbolic creatures maintain their power to inspire creative interpretation across changing artistic movements and periods.

The Kristal calendar, created to promote photographer Frank Philippi's photo studio, features a striking crystal glass bowl adorned with mythological female figures.

This promotional piece demonstrates how mythological imagery permeates even commercial design, blending intricate glasswork with classical representations of female forms. Philippi's artistic approach combines photography with mythological symbolism, creating a visual language that draws on shared cultural references to elevate a commercial object into something more evocative.

The piece exemplifies how mythological references function as a visual shorthand across cultures and contexts, lending gravitas and artistic legitimacy to everyday objects and promotional materials.

Ireland's journey in the 1990 World Cup offers a compelling case study in how sporting events transform into powerful national mythology. What began as a football tournament became a transcendent cultural moment, demonstrating how societies create narratives that far exceed the literal significance of the events that inspired them.

Set against a backdrop of economic hardship and political uncertainty, Ireland's unexpected success under Jack Charlton provided not merely entertainment but a canvas onto which collective hopes and anxieties could be projected. The nation's first ever World Cup saw the team progress to the quarter-finals catalysing a nationwide catharsis, temporarily unifying a society often divided by political tensions and social challenges. This phenomenon represents a classic example of how successful national mythologies often emerge from moments of shared emotional experience rather than rational planning.

The mythological resonance of Italia '90 invokes universal archetypal patterns—the underdog's journey, the symbolic battle against powerful opponents, the testing of national character on an international stage. The iconic images of packed pubs and streets filled with celebrating crowds have become ritualistic scenes in Ireland's collective memory, functioning as visual shorthand for a moment when national identity was intensely felt rather than merely conceptualised.

Perhaps most significantly, Italia '90 demonstrates how contemporary societies still create and consume mythology in ostensibly secular and rational contexts. The tournament's elevation from sporting event to national touchstone reveals the persistent human need for shared narratives that transcend individual experience. Like all effective mythologies, its power lies not in factual achievements but in symbolic resonance—creating a narrative that continues to function as an emotional reference point in Irish cultural consciousness, far exceeding its significance as a mere football tournament.

Močiute mano, senoji mano, kam mane mažą valioj auginaii is a traditional Lithuanian folk song recorded by the influential 19th-century scholar Jonas Basanavičius, often regarded as the patriarch of the Lithuanian National Revival.

Sung by villagers from Dziegcioriai village in what is now Lithuania, this song reflects deeply embedded cultural themes of intergenerational relationships, familial bonds, and the passage from childhood to adulthood. The narrative voice questions the grandmother about the purpose of nurturing and raising a child with such care, expressing a poignant reflection on the cycle of life and responsibility.

The song belongs to Lithuania's rich tradition of folk music, which has served as a crucial repository of cultural memory and identity, particularly during periods when Lithuanian national identity was suppressed under various occupations. Folk songs like this one preserved linguistic traditions, cultural values, and historical memory when formal institutions could not.

The archiving of such cultural expressions by the Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos instituto Lietuvių tautosakos archyvas, (Lithuanian Folklore Archives of the Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore) represents a vital effort to preserve intangible cultural heritage. This preservation allows contemporary audiences to engage with traditional expressions of community values and shared experiences that might otherwise be lost.

Through such folk songs, we can observe how oral traditions serve as vehicles for cultural transmission, conveying wisdom, values, and emotional experiences across generations, maintaining continuity while allowing for adaptation to changing social contexts.

William Elliot Griffis's collection Belgian Fairy Tales represents a significant contribution to the preservation and transmission of European folkloric traditions at a time when rapid industrialisation threatened traditional oral cultures. As part of Griffis's broader project documenting global folklore—including Dutch, Japanese, and Korean tales—this work demonstrates the universal human tendency to create explanatory narratives while highlighting the distinctive cultural elements that make Belgian traditions unique.

Specifically aimed at young readers, this collection exemplifies how traditional folkloric material was adapted and recontextualised for modern audiences in the early 20th century. The deliberate framing of these tales for children reflects a broader cultural shift in which folklore—once an integral part of communal life for people of all ages—became increasingly categorised as children's literature. This transformation fundamentally altered how such narratives functioned in society, changing them from multivalent cultural resources into primarily pedagogical or entertainment tools.

The rich illustrations featured throughout the volume serve not merely as decorative elements but as essential components of the storytelling experience, creating visual entry points into the narrative world. This integration of text and image creates a multisensory experience that, while different from traditional oral storytelling, offers its own form of immersive engagement with cultural mythology.

Griffis's work as a collector and adapter of global folklore positioned him within a broader international movement to document and preserve traditional narratives during a period of rapid social change. This comparative approach to mythology anticipated modern understanding of how similar narrative patterns emerge across cultures while manifesting in culturally specific forms. His collection thus stands as both a cultural artifact of early 20th century approaches to folklore and a valuable preservation of traditional Belgian narrative traditions.

Bluiríní Béaloidis is a podcast from the National Folklore Collection at University College Dublin. It explores the rich landscape of Irish and European folk traditions. Each episode journeys through diverse cultural narratives, revealing how understanding our traditional heritage can illuminate our present and guide our future. By uncovering the stories, beliefs, and practices embedded in folklore, the podcast invites listeners to discover the depth and complexity of our shared cultural inheritance.

Bile Buaice

This episode of Blúiríní Béaloidis explores how trees have functioned as powerful symbolic mediators between earthly and divine realms across human cultures. By examining trees' unique qualities—simultaneously rooted in earth while reaching skyward, embodying cycles of growth, maturity, decay, and renewal—hosts Jonny Dillon and Claire Doohan illuminate how natural forms provided traditional societies with sophisticated frameworks for understanding cosmic structure and human relationship to it.

The discussion of sacred trees under which Irish kings were inaugurated demonstrates how natural features acquired political and religious significance through ritual practice. These trees functioned not merely as convenient meeting places but as living embodiments of cosmic order that sanctified political authority by connecting it to broader patterns of cosmic structure. This integration of natural forms into political ritual exemplifies how traditional societies embedded governance within comprehensive mythological frameworks rather than treating it as separate secular domain.

The exploration of hallowed groves that provided refuge for both saints and madmen reveals how certain natural spaces were understood as liminal zones where normal social boundaries temporarily dissolved. These sacred spaces facilitated encounters with divine or supernatural presences that might be dangerous but also potentially transformative. The tradition of leaving votive offerings on trees near holy wells further demonstrates how natural features functioned as interfaces between human and divine domains, facilitating communication across cosmic boundaries.

The hosts' invitation to shelter "beneath the metaphorical canopy of tradition" exemplifies how contemporary engagement with folkloric materials can provide meaningful frameworks for understanding cultural heritage. By exploring historical beliefs about sacred trees, the podcast demonstrates how traditional ecological knowledge was embedded within mythological frameworks that simultaneously explained natural phenomena and provided guidelines for human interaction with the environment. These traditions thus represent not primitive misunderstandings but sophisticated cultural adaptations that helped human communities navigate their relationship with the natural world.

The series offers a comprehensive exploration of how Ireland, as a new nation-state, evolved a collective identity over its first seven decades. The shared national narrative, initially framed by founding leaders, evolved through a dynamic interplay of internal and external socio-economic-cultural forces. It reveals the complex process through which societies construct and sustain their sense of collective self

Episode 4 examines how economic challenges in 1950s Ireland catalysed a profound national reckoning with competing mythologies of identity. The clash between romantic pastoral ideals and modernisation imperatives reveals a universal pattern in how societies negotiate transitions through competing narratives of who they are and who they might become.

Seán Ó Mórdha's documentary series presents this period as a critical juncture where Ireland's self-conception was fundamentally contested, illustrating how economic necessities often force reconsideration of cherished national myths. The series demonstrates that moments of economic crisis frequently trigger not just policy debates but deeper existential questions about national character and purpose.

Each episode explores decisive moments in Ireland's evolution, revealing how national identities are constantly renegotiated through an ongoing dialogue between established narratives and emerging realities. The documentary features insights from key political figures and cultural commentators, offering multi-dimensional perspectives on Ireland's struggle to reconcile traditional self-conceptions with modern imperatives.

By examining the tension between idealised pasts and pragmatic futures, the series provides a sophisticated framework for understanding how societies adapt their foundational stories to accommodate changing circumstances. First broadcast in 2000, Seven Ages continues to offer valuable insights into how national mythologies function both as anchors to tradition and as adaptable frameworks that can accommodate—albeit sometimes reluctantly—the inevitability of change.Seven Ages: The Story of the Irish Stateis a landmark documentary series produced in 2000 by Araby Productions for RTÉ and BBC Northern Ireland. Directed by Seán Ó Mórdha, this influential seven-part series chronicles Ireland's evolution since its founding in 1921 through key political, social, and cultural moments in history.

This engraving of Neptune and Amphitrite's Triumphal Chariot, created for the 1599 joyous entry of Archdukes Albert and Isabella into Antwerp, exemplifies how classical mythology served essential political functions in early modern European court culture. Designed by Joos de Momper and engraved by Pieter van der Borcht in 1602, this copper engraving represents the sophisticated integration of mythological references into public ceremonial designed to legitimise political authority.

The "joyous entry" tradition itself functioned as a ritual performance that established mutual obligations between rulers and cities. By incorporating classical deities into these ceremonies, organisers created symbolic frameworks that positioned contemporary rulers within established patterns of legitimate authority. Neptune, as god of the sea, held particular significance for maritime powers like the Spanish Netherlands, creating resonance between mythological references and practical concerns of trade and naval power.

The translation of ephemeral ceremonial elements into permanent engraved form represents an important aspect of how such mythological performances extended their influence beyond immediate participants. Connected to Joannes Bochius' historical narrative of the event, this engraving transformed temporary spectacle into lasting documentation, allowing the symbolic frameworks established during the ceremony to circulate more widely and persist over time.

This artifact demonstrates how classical mythology provided Renaissance and Baroque societies with sophisticated visual language for articulating political relationships and aspirations. By invoking Neptune and Amphitrite in ceremonial contexts, organisers drew on established symbolic associations while adapting them to address contemporary political circumstances. The Museum Plantin-Moretus' preservation of this engraving reflects ongoing cultural interest in understanding how mythological frameworks shaped political culture during this formative period of European state development.

This Baltic brass ring featuring serpent motifs exemplifies how mythological understanding was incorporated into everyday objects. Drawing inspiration from archaeological findings, the ring embodies ancient Baltic cosmological concepts through its symbolic imagery and circular form.

The serpent, a potent symbol in Baltic mythology as in many world traditions, carried multiple associations—justice, domestic happiness, and protection. This multivalent symbolism demonstrates how mythological figures often function simultaneously across several conceptual domains, collapsing distinctions between moral, emotional, and practical concerns. The serpent's ability to shed its skin made it a natural symbol of renewal and transformation across many cultures, while its movement between surface and underground realms positioned it as a mediator between worlds.

The ring form itself, with no beginning or end, provided a natural vehicle for expressing cyclical time—a fundamental concept in traditional Baltic worldviews governed by seasonal rhythms and astronomical cycles. By wearing such symbols on the body, individuals incorporated themselves into cosmic patterns while simultaneously marking cultural belonging through distinctive stylistic execution.

The craftmanship evident in such pieces reflects the sophisticated metalworking traditions of Baltic peoples, where technical skill itself was understood within a mythological framework. The transformation of raw materials into meaningful forms through the application of fire and specialized knowledge carried associations with creative and even magical processes. This ring thus demonstrates how material culture in traditional societies operated simultaneously across practical, aesthetic, and spiritual domains, embedding cosmic understanding in the most personal of objects.

This woodcut used for the title page of Francisco Aguilonius' scientific work on optics exemplifies how Renaissance and early modern scientific publications incorporated mythological imagery even as they advanced empirical understanding of natural phenomena. Created in the Officina Plantiniana printing press in Antwerp, the frame adorned with various mythological figures demonstrates the complex relationship between emerging scientific methodologies and established symbolic frameworks during this transitional period in European intellectual history.

The integration of classical mythological references in a scientific work on optics reflects the Renaissance understanding of knowledge as an integrated whole rather than a collection of discrete disciplines. By framing scientific content with mythological imagery, the publication positioned new optical discoveries within established intellectual traditions while simultaneously signaling its participation in humanist cultural innovations. This visual rhetoric exemplifies how early modern scientific communication operated within broader cultural frameworks rather than as a completely separate domain.

The specific choice of mythological figures likely created meaningful connections between classical traditions and the optical content of Aguilonius' work. Light, vision, and perception were subjects of significant interest in classical mythology and philosophy, providing rich symbolic resources for visual representation of optical principles. This deliberate connection between ancient and modern approaches to similar phenomena exemplifies how Renaissance thought evolved through dialogue with classical precedents rather than through complete rejection of earlier frameworks.

The preservation of this woodcut in the Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp reflects ongoing cultural interest in understanding how visual culture participated in the complex evolution of scientific thought. Rather than representing a clean break with earlier modes of understanding, scientific illustration during this period demonstrates how new empirical approaches emerged gradually from within established intellectual frameworks, incorporating elements of traditional symbolic thinking while developing increasingly systematic approaches to natural phenomena.

Perkūnas stands as one of the most powerful and revered deities in the Baltic pantheon, central to Lithuanian pagan traditions dating back to the pre-Christian era. This thunder god plays a multifaceted role as nature's protector, fertility bringer, and justice enforcer, embodying the dynamic and often unpredictable power of atmospheric phenomena.

Deeply connected to seasonal cycles, Perkūnas is renowned for his thunderbolts, which are said to fertilise the earth goddess Žemyna during spring's first storm, awakening nature from winter dormancy and initiating the annual cycle of growth and renewal. This connection between celestial and terrestrial fertility reflects the agricultural foundations of Baltic spiritual traditions.

Perkūnas is typically depicted wielding weapons like the "god's whip" (lightning) or stone axes, which he uses to punish wrongdoing and maintain cosmic order. His character as a just, if sometimes impatient, guardian of morality is exemplified in his rivalry with Velnias, a deity associated with chaos and the underworld. This duality underscores the balance between light and darkness, order and chaos in Baltic mythological understanding.

Rituals honouring Perkūnas included sacrifices, prayers for favourable weather, and offerings of grain or livestock. People sought his protection during storms by adorning homes with sacred tree branches or ringing bells to repel evil spirits. Thunder was interpreted as Perkūnas' voice, through which he communicated with priests who would lead communities in sacrifices and celebrations.

The enduring significance of Perkūnas in Lithuanian folklore illustrates how mythological figures can embody both natural forces and moral principles, providing frameworks for understanding both the physical world and ethical behaviour.

Jan Matejko's painting Vernyhora, begun in the 1870s and completed in 1884, represents a significant artistic engagement with a semi-mythical figure who occupies a unique position in both Ukrainian and Polish cultural memory. Currently housed in the National Museum in Kraków, this work demonstrates how historical and legendary narratives can be visually reinterpreted to address contemporary national concerns.

Vernyhora, a Ukrainian bard and lyricist who may have lived during the late 18th century, inhabits the ambiguous boundary between historical figure and mythological construct. Living during a period of anti-noble uprisings in Ukraine, he allegedly opposed the prevailing movements and became renowned for his prophetic visions concerning the intertwined fates of Poland and Ukraine.

These prophecies, which reportedly foretold the partitions of Poland, the failure of national uprisings, and the eventual revival of Polish statehood, secured Vernyhora's place in the cultural imagination of both nations. His liminal status—between Ukrainian and Polish worlds, between historical fact and legend—made him a particularly potent symbol during the 19th century, when questions of national identity and independence were paramount concerns.

Matejko, Poland's foremost historical painter, captures Vernyhora at the moment of delivering his prophecy. The figure is depicted wearing an eastern cross on his chest, symbolising the ancient unity of Ukraine and Poland—a time of supposed national and social harmony before the violent upheavals of the 18th century. The lyre at his feet further signifies the power of artistic expression to preserve shared cultural heritage despite political and historical divisions.

This painting exemplifies how mythologised historical figures can be mobilised in times of national crisis to articulate aspirations for cultural continuity and political restoration, demonstrating the fluid boundaries between history, myth, and political symbolism.

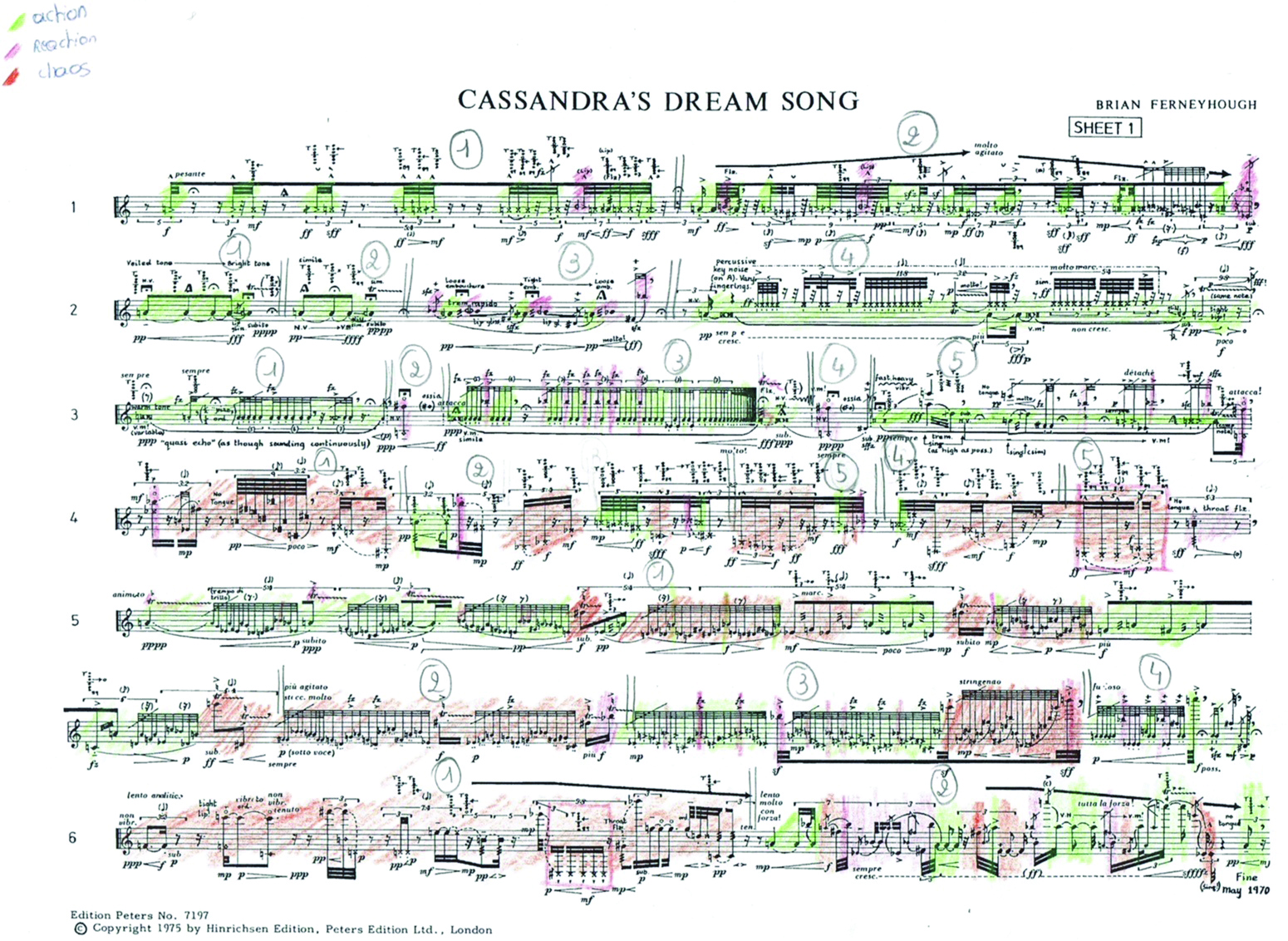

Brian Ferneyhough's Cassandra's Dream Song (1970) and its subsequent interpretations offer a fascinating case study in how classical mythological figures continue to function as potent vehicles for exploring contemporary concerns. By invoking Cassandra—the Trojan princess whose true prophecies were doomed to be disbelieved—the composition creates a multilayered reflection on communication, truth, and the limitations of human understanding.

The controversy surrounding gendered interpretations of the piece demonstrates how mythological references serve as cultural battlegrounds where competing values and perspectives contend for interpretive authority. Traditional readings that emphasised stereotypical female suffering collided with contemporary psychological approaches that sought to explore the complexity of Cassandra's inner conflict and prophetic burden. This interpretive evolution reflects broader societal shifts in understanding gender and psychological experience.

Particularly significant is flutist Ine Vanoeveren's "restyling" of the work, which reimagines it through a contemporary psychological lens. This approach exemplifies how mythological figures maintain relevance through continuous reinterpretation—each generation finds new meaning in ancient archetypes by applying current frameworks of understanding. Vanoeveren's approach demonstrates how performers themselves participate in mythological evolution, bringing new perspectives to established narratives.

The intersection of complexity music and psychological themes in this composition reveals how contemporary artistic practices often serve functions similar to traditional mythology—creating frameworks for exploring aspects of experience that resist simple articulation. By evoking Cassandra's tragic position, Ferneyhough's work addresses fundamental human concerns about knowledge, belief, and communication that transcend specific historical contexts. The ongoing reinterpretation of this piece demonstrates how mythological references continue to provide flexible frameworks for examining evolving cultural concerns.

Seven Ages: The Story of the Irish Stateis a landmark documentary series produced in 2000 by Araby Productions for RTÉ and BBC Northern Ireland. Directed by Seán Ó Mórdha, this influential seven-part series chronicles Ireland's evolution since its founding in 1921 through key political, social, and cultural moments in history.

The series offers a comprehensive exploration of how Ireland, as a new nation-state, evolved a collective identity over its first seven decades. The shared national narrative, initially framed by founding leaders, evolved through a dynamic interplay of internal and external socio-economic-cultural forces. It reveals the complex process through which societies construct and sustain their sense of collective self

Episode 5 analyses how Ireland's cultural opening in the 1960s represents a fascinating case study in the evolution of national mythologies. The emergence of a new narrative centred on progress and modernity reveals the dynamic nature of collective storytelling, showing how societies periodically reformulate their foundational myths to accommodate changing social conditions and aspirations.

Seán Ó Mórdha's documentary series presents this period as a pivotal moment where Ireland began consciously revising its self-conception, illustrating how national identities are not fixed but continuously negotiated. The series demonstrates that such cultural shifts are rarely complete ruptures with the past but rather reinterpretations that incorporate new elements while maintaining narrative continuity with established traditions.

Each episode examines crucial developments in Ireland's evolution, revealing how national mythologies serve both as reflections of social change and as frameworks that shape how those changes are understood and integrated. The documentary features perspectives from influential figures in Irish politics and culture, offering insights into how those at the centre of transformative periods perceive and articulate emerging narratives.

By analysing the interplay between tradition and innovation in national storytelling, the series provides a nuanced understanding of how societies manage cultural transitions. First broadcast in 2000, Seven Ages remains a valuable resource for understanding how national identities evolve through an ongoing dialectic between established narratives and emerging social realities, demonstrating that the stories nations tell about themselves are always works in progress.

This collection of folk stories from Flanders and Brabant represents a significant preservation of oral traditions at a time when such cultural expressions were increasingly threatened by modernisation. Featuring tales like Simple John and The Boy Who Always Said the Wrong Thing, the collection offers valuable insights into the moral frameworks and imaginative patterns that shaped traditional Flemish culture.

The collection's emphasis on "simple, sometimes primitive characters" reflects the didactic function of folk narratives across cultures. By presenting protagonists who initially lack wisdom or sophistication but navigate challenging situations, these tales provide accessible models for moral development and practical problem-solving. Their "whimsical adventures" create engaging narrative frameworks for exploring the consequences of various choices and behaviours.

The comparison to nursery rhymes in other cultures acknowledges the multilayered functionality of folk narratives, which simultaneously entertain, instruct, and transmit cultural values. This combination of purposes distinguishes traditional storytelling from more specialised modern narrative forms, reflecting pre-modern integration of education, entertainment, and moral instruction rather than their separation into distinct domains.

The translation of these tales into English by M.C.O. Morris represents a significant cultural transition, transforming localised oral traditions into internationally accessible literary artefacts. This process, paralleled across Europe during the 19th and early 20th centuries, fundamentally altered how folk narratives functioned—preserving them while simultaneously changing their context and meaning. The illustrations by Jean de Bosschère further adapt these oral traditions to visual form, creating a multisensory experience that differs from traditional storytelling while making the narratives accessible to new audiences.

Talking History offers a distinctive exploration of pivotal political, social and cultural events that have shaped our world, examining the complex figures central to these historical moments. Hosted by Dr Patrick Geoghegan of Trinity College Dublin, this programme interrogates the multifaceted, often contested dimensions of our collective past, illuminating what these historical narratives reveal about contemporary society.

The Irish Wake

This right of passage represents one of Ireland's most distinctive cultural traditions, a complex ritual that has evolved over centuries to address the universal human experience of death through distinctively Irish practices and perspectives. More than simply a funeral rite, the Wake embodies a unique expression of how Irish communities have traditionally coped with, commemorated, and even celebrated the passage from life to death.

This episode of RTÉ's "Talking History" with Patrick Geoghegan explores the rich history of Irish wakes, examining their development and significance across centuries. The programme was inspired by the opening of Ireland's first dedicated Irish Wake Museum at Waterford Treasures, which preserves and showcases this important aspect of cultural heritage that risks being lost in an increasingly secularised and medicalised approach to death.

Traditional Irish wakes combined elements of Christian ritual with pre-Christian practices, creating a distinctive approach to death that emphasised community solidarity, storytelling, and often humour in the face of loss. The body would typically be prepared at home and laid out in the best room of the house, with visitors coming to pay respects over several days. These gatherings featured a characteristic blend of solemnity and sociability, with prayer sessions interspersed with storytelling, music, food, drink, and occasionally games.

As noted by comedian Dave Allen, whose observations are featured in the programme, Ireland developed a distinctive cultural approach to death that acknowledged its inevitability while finding ways to celebrate life in its presence. Allen describes the wake as a "marvellous celebration" that could transform even the death of an unpopular community member into an occasion for gathering and storytelling.

This tradition exemplifies how communities develop cultural practices to make meaning from mortality, creating shared narratives and rituals that provide structure and comfort during times of loss while reinforcing social bonds and collective identity.

Seven Ages: The Story of the Irish Stateis a landmark documentary series produced in 2000 by Araby Productions for RTÉ and BBC Northern Ireland. Directed by Seán Ó Mórdha, this influential seven-part series chronicles Ireland's evolution since its founding in 1921 through key political, social, and cultural moments in history.

The series offers a comprehensive exploration of how Ireland, as a new nation-state, evolved a collective identity over its first seven decades. The shared national narrative, initially framed by founding leaders, evolved through a dynamic interplay of internal and external socio-economic-cultural forces. It reveals the complex process through which societies construct and sustain their sense of collective self

Episode 2 analyses how Éamon de Valera's Fianna Fáil fundamentally reshaped Ireland's political landscape by skilfully harnessing cultural mythology as a political tool. The party's deliberate promotion of traditional Irish values was a sophisticated exercise in narrative construction, connecting contemporary political aims with selective interpretations of cultural heritage to reinforce a cohesive national story.

Seán Ó Mórdha's series illuminates the complex relationship between political power and cultural narrative, demonstrating how emerging nations often look backward to move forward. The series shows how de Valera's Ireland exemplifies a universal pattern in which new political orders establish legitimacy by positioning themselves as natural inheritors of an idealised past.

Each episode reveals critical moments where Ireland's self-conception was challenged, negotiated, and reformulated, highlighting the essential role of storytelling in political legitimation. The documentary features insights from key political figures including former Presidents and Taoisigh who themselves participated in the evolution of Ireland's national narrative.

By examining the interplay between political pragmatism and cultural symbolism, the series offers profound insights into how national identities are deliberately crafted to serve contemporary needs. First broadcast in 2000, Seven Ages continues to provide valuable perspective on how societies create coherent narratives from complex and often contradictory histories, showing that the mythologies that bind us together are as much inventions as discoveries.

This traditional Lithuanian folk song, recorded by the influential 19th-century scholar Jonas Basanavičius (1851-1927), represents a significant element of Lithuania's intangible cultural heritage. Sung by villagers from Dziegcioriai, the song exemplifies how oral traditions preserve cultural knowledge, values, and emotional experiences across generations.

The title, which translates as "The Mother Sent, the Heart Sent, to the Waters of the Danube," immediately establishes key themes found throughout Baltic folk traditions: the connection between family relationships, emotional experience, and natural elements. The reference to the Danube River is particularly interesting, as it demonstrates how geographical features can take on symbolic significance even in regions where they are not physically present, likely entering Lithuanian folklore through broader European cultural exchanges.

The song's structure and content would typically reflect traditional Lithuanian folk music characteristics, including pentatonic scales, parallel harmonies, and themes related to family relationships, agricultural cycles, or emotional experiences. Such songs often feature repeated melodic phrases with subtle variations, creating both familiarity and continuous development throughout the piece.

Basanavičius's work in documenting such folk expressions was crucial to the Lithuanian National Revival movement, which sought to preserve and celebrate Lithuanian cultural identity during a period when it was threatened by Russification policies under Tsarist rule. The preservation of these cultural expressions by the Lietuvių literatūros ir tautosakos instituto Lietuvių tautosakos archyvas (Lithuanian Folklore Archives of the Institute of Lithuanian Literature and Folklore) ensures this heritage remains accessible for future study and appreciation.